The next edition of FiltXPO, North America’s technical conference and exhibition for the filtration and separation industry, will be presented March 29-31, 2022, in Miami Beach. The event will feature five panel sessions focused on how filtration can address today’s societal challenges related to the pandemic, environmental sustainability, climate change and other issues. As we lead up to this event, IFN is featuring roundtable Q&As with FiltXPO panelists around the topics they will be discussing at the conference. The first installment in this series, “Filtration standards – friend or foe?” appeared in Issue 5 2021 of IFN, and can be found at bit.ly/filtrationstandards. Part II in the series, “Sustainability in filtration,” appeared in Issue 6, and can be found at bit.ly/sustainabilityinfiltration.

The following roundtable focuses on how the COVID-19 pandemic has, and will, change the filtration industry, with comments from Wade Conlan, Hanson Professional Services and the ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force Building Readiness Team, Jonathan Szalajda, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, NIOSH, Behnam Pourdeyhimi, Ph.D., North Carolina State University and The Nonwovens Institute, and Thad Ptak, Principal, Ptak Consulting.

Wade Conlan

PE, CxA, Hanson

Professional Services, Inc.

Wade Conlan is an expert in the design, troubleshooting, and optimization of HVAC systems with an engineering and project management background. He is responsible for design review, submittal review, commissioning plans, functional tests, performance tests and lifecycle analysis. Conlan has been the project manager and commissioning engineer for over 60 million sq.ft of facilities around the world, and he currently leads the ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force Building Readiness team. He can be reached at +1 321.214.9303 or wconland@hanson-inc.com.

Behnam Pourdeyhimi, Ph.D.

North Carolina State University

The Nonwovens Institute

Behnam Pourdeyhimi, Ph.D., is the William A. Klopman Distinguished Professor of Materials in the Wilson College of Textiles at NC State and is an affiliated professor in the departments of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. He also serves as Associate Dean in the Wilson College of Textiles and is the Executive Director of The Nonwovens Institute. Dr. Pourdeyhimi is world renowned for his contributions to nonwovens and the establishment and growth of nonwovens at NC State. He can be reached at +1 919.515.1822 or bpourdey@ncsu.edu.

Thad Ptak, Ph.D.

Principal

Ptak Consulting

Thad Ptak, Ph.D., has more than 30 years of experience in filtration technologies, aerosol science and indoor air quality. He has conducted extensive research in the areas of development of filter media and filters, portable air cleaners, indoor air quality, sensors for IAQ and instrumentation for particle generation and measurement. He has been involved in research, development and manufacturing in consumer products, HVAC, portable air cleaner and automotive filtration and is an active participant in industry societies and standards committees. He can be reached at +1 414.514.8937 or thadptak@hotmail.com.

Jonathan Szalajda

NIOSH, Centers for Disease Control

& Prevention

Jonathan Szalajda serves as deputy director for the National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) division of The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in September 2015. Since joining NPPTL in 2001, he has held various leadership roles in the organization. Some of his duties have included development of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)-related standards and regulations, including NIOSH’s Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) respirator standards. He can be reached at zfx1@cdc.gov.

How has COVID-19 changed the filtration industry?

Wade Conlan, PE, CxA, Hanson Professional Services, Inc.: There are two things that really jump out when I think about filtration in the light of COVID-19. The first one is the MERV rating of your filter and what you actually have in your system today – your pre-COVID filtration, and then what you’re actually able to get the system to accommodate. The ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force has recommended MERV-13 filters across the board, because they have to take into account one-inch filters for residential and two-inch filters for a lot of smaller equipment. And so, trying to make sure that people understand, one, what filters do you have? What is its MERV rating? And then, can you get your system to be MERV-13 or better?

The other component that really comes into filtration is less about the actual rating, but it’s maintaining that rating by making sure the filter is installed properly.

When you install a filter with gaps, or just not well enough, its performance is greatly reduced. You’re buying this great

MERV-13, MERV-14 filter, and then it’s operating like a MERV-8. So, you’re losing all of the benefit of a better filter, which you’ve paid an additional amount for. That can be checked by the facility directors and maintenance staff by doing integrity tests.

And so, those are the two things that come to mind: An increased need to determine what filters do I have?/What level can I get to?; and then, how well am I installing that filter? These are the real COVID drivers that I see for filtration. There are a few other items, such as MERV or MERV-A, but then we start to get into the weeds.

Behnam Pourdeyhimi, Ph.D., North Carolina State University, The Nonwovens Institute: One of the key lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic is that charged meltblown media remains the only viable technology for facemasks. Electrospun webs typically end up with a higher pressure drop, and a lack of knowledge in how to form a “good” filter is still an issue. A trial-and-error approach to product development is an issue.

Indoor environmental quality is going to become more important going forward. We’re already seeing it in designs. We’re seeing individuals include what’s called “Pandemic Mode” for how the equipment or system should operate. Think of it as an emergency generator kicking on when you lose utility power. – Wade Conlan

– Wade Conlan, Hanson Professional Services, Inc., ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force Building Readiness Team

When it comes to products like facemasks, for example, the pandemic has also shown that it is difficult to produce them quickly and distribute them equitably to low- and middle-income countries. A paradigm shift is needed, and cloth masks are not the solution.

Thad Ptak, Principal, Ptak Consulting: The biggest change is related to the domestic manufacturing capacity for masks and respirators. As of now, the U.S. estimated production capacity for these products has exceeded the estimated domestic demand. This is a significant change from 2019 when approximately 75% of masks were imported.

Another big change is the increased manufacturing capacity for polypropylene meltblown materials used in masks and respirators, as well as in HVAC filters.

Jonathan Szalajda, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, NIOSH: In response to the pandemic, The U.S. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) more than doubled respirator investigations and approval decisions in 2020 and 2021. These efforts substantially increased the inventory of respirators across the country. Both experienced and new respirator manufacturers report substantial inventory on hand.

Based on distributor deliveries, N95 demand increased sharply during the late summer COVID-19 surge, and has since tapered off, with projected steady state demand assuming current COVID-19 protocols stay in place. The U.S. Strategic National Stockpile, FEMA, and states have collectively stockpiled N95s and other PPE. If industry is unable to provide any capacity, the stockpiles can provide time for manufacturers to ramp up production in the case of another pandemic-like crisis. In addition, the requirement for medical-grade masks per month can be met domestically, assuming max capacity level of production.

Where do you see the big opportunities for innovation in filtration in light of the pandemic?

Behnam Pourdeyhimi: Smarter machinery – current technologies are automated, but the operator still has to know how to make a filter by adjusting various process parameters. Smarter machinery that is fully instrumented is badly needed. Charge stability is a major issue, as we saw the majority of the expired stockpile masks during the pandemic had lost their charge and their efficiency had fallen below acceptable levels.

I believe we are not ready for another pandemic yet. Manufacturing innovations are badly needed, and we need a better approach to designing filters for masks.

– Behnam Pourdeyhimi, Ph.D., North Carolina State University, The Nonwovens Institute

The pressure drop in masks is too high, as the NIOSH inhalation and exhalation pressure drops have created a low barrier to entry. Therefore, today, one can find masks that have very high pressure drops while others are more comfortable. This needs to be revisited. Designing a better mask that offers good breathability (lower pressure drop) is essential, especially when masks are worn for extended periods or for those who have medical conditions (heart and lung issues) and children.

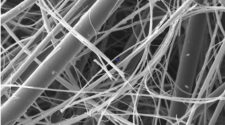

Mask filters are almost exclusively made from electrostatically charged polypropylene (PP) meltblown (MB) nonwovens. MB filters have fibers in the range of 0.5 to 5 microns in size and are therefore, fragile and must be protected by layers of spunbond (SB) PP made up of larger fibers — 15 to 25 microns — which provide mechanical protection for the MB filter layer.

The dual challenge faced in the United States and globally during the COVID-19 pandemic was the limited production of MB fabric and the lack of infrastructure needed to convert the fabrics into masks.

MB and SB production facilities are always custom built, are large and expensive and require significant infrastructure. The lead time for setting up new capabilities is typically greater than 10 months at a cost of more than $10 million for a small, 1.6-meter-wide meltblowing machine. Therefore, even in high-income regions in North America and the European Union, plants could not be deployed any faster. In other regions of the world, it would be impossible to ramp up quickly, and this is why there needs to be a paradigm shift. In contrast, mask conversion is more readily available, is relatively inexpensive and does not require special infrastructure.

MB machines are a lot more expensive than the sum of their components. Engineering know-how and in some cases, intellectual property, create barriers to entry. Meltblowing, for example, is rather simple as a process. The key to the technology is the die tip that controls the uniformity of the fibers produced. The rest of the components are off-the-shelf. However, the nonwoven industry is built around large volumes, high speed and low production costs, and automation. This is why the nonwoven industry continues to lead the world in productivity and innovation.

What is needed for such products as face masks and respirators is a different solution. The mask conversion is also a fully automated process, and the width requirements range from 19.5 centimeters (cm) to 32 cm at most. Note that mask converting does not require special infrastructure such as high bay space, for example. If a MB machine was designed that is only say 40 cm wide, the process will still be fast enough to supply many mask converting machines while the costs will be low, and no special infrastructure is needed. The Biax Fiber Film pilot line is an example of how to remodel existing pilot lines to increase output within a small footprint. With a few minor changes, this can become a super mask filter production machine that can also be collocated with the mask converting equipment. There are other examples of such smaller footprint lines that are primarily used as pilot lines. Such designs can be replicated and reproduced easily as needed.

Thad Ptak: The biggest challenge is not as much the filtration technology as the execution. By this, I have in mind commercial and residential HVAC systems, especially residential homes. Majority of residential systems are designed for low Total External Static Pressure, (TESP). New filters with higher pressure drop and especially dust loaded filters can reduce the flow rate of the system by 200-250 CFM, depending on the system design and type of motor. Lower flow rate can result in reduced cleaning effectiveness, since the system cleaning effectiveness depends on the flow rate and filtration efficiency.

Another critical aspect is the system runtime which is defined as a fraction of time the HVAC system operates. Typically, the average runtime for residential application is in range of 6-8 hrs./day.

Filters with E2 efficiency (for particles 1-3 micrometers) greater than 80-85% (MERV 12/13) should be effective in removing of airborne bioaerosols, assuming the system is operating properly. However, the performance degradation of filters made of electrostatically enhanced filter media is another critical issue which can have a negative impact on system effectiveness.

Jonathan Szalajda: Masks produced to recognized consensus standards are also available. ASTM International developed a new Barrier Face Covering (BFC) standard (number F3502-21) to establish a set of uniform testing methods and performance criteria. The development of this ASTM International standard provides a consistent baseline that allows comparison of product claims in terms of filtration efficiency, breathability, re-use potential and leakage. To meet the ASTM standard, a BFC must meet certain design and performance requirements, including filtration efficiency and air flow, which must be tested by an accredited laboratory and labeled accordingly. A list of manufacturers who claim conformance to this new ASTM standard can be found at wwwn.cdc.gov/PPEInfo/RG/FaceCoverings.

ASTM International developed a new Barrier Face Covering (BFC) standard (number F3502-21) to establish a set of uniform testing methods and performance criteria. The development of this ASTM International standard provides a consistent baseline that allows comparison of product claims in terms of filtration efficiency, breathability, re-use potential and leakage.

– Jonathan Szalajda, NIOSH, U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention

Wade Conlan: I think, in most industries, what you’re seeing is people don’t know what they have for filtration. They have whatever the engineer designed it for, or whatever the maintenance guy could get a deal. I’ve gone into buildings and evaluated their filters. I’ve seen MERV 5 filters. I’ve even seen MERV 4 filters installed for commercially occupied spaces. They’re doing it to save cost on the filter or cost on the operation. They have what they have because that’s what the designer put on drawings many years ago, and they haven’t necessarily evaluated it for their process or for their space use.

I lead the Building Readiness Guide Team for the ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force, and we’re actively discussing how to evaluate your building and your systems, whether it’s your building automation system, your chilled water system, your air handling units, or your outdoor air.

Importantly, your filters and making sure what you have. There was a study that the U.S government did for educational facilities and their HVAC systems. It showed that more than 50% of the buildings had systems that were either past their expected useful life or they were not working. Think of all the schools around the U.S. Say that, on average, 50% are not working. That means you’ve got 50% of your buildings that are probably not up to the appropriate level for being occupied safely or as safe as you can make it.

That’s the interesting piece. OSHA is talking about COVID-19, potentially, as a workspace hazard — just like a trip, a fall, a slip and how it has to be reported. Well, if that’s the case, then if you’re not doing what you need to appropriately, and when you see most of those OSHA cases, have you done what’s reasonable to keep people safe? If your filtration is poor and your systems aren’t working, then it’s less likely that you are providing an adequate space for those individuals, and that could be a pretty big deal. Now, of course, that is still being bandied about in the courts, if you will. But that’s where they’re headed — is making [IAQ] a workplace hazard, and so that changes how you have to address it.

How prepared do you believe the filtration industry and/or the current filtration technology is for the next pandemic – particularly for indoor air quality, and facemasks … do you see any supply chain issues?

Thad Ptak: As of now, with the sufficient manufacturing capacity for masks and meltblown, it looks good. However, there are already signs that the capacity can go away as the pandemic dies down. Cost issues and pressure from low-cost manufacturing in China can also have a negative impact on capacity.

Residential filtration could benefit from changes to the HVAC system. New systems should allow for installation of larger filters, 2” and 4” deep, and they should be designed for higher total external static pressure (TESP).

Jonathan Szalajda: The PPE commodity domain in our domestic supply chain has seen significant improvements in almost every category, including respirators and face coverings, with investments putting us in a significantly better posture than before COVID-19, both in amounts stored in the Strategic National Stockpile and industrial manufacturing capacities.

Wade Conlan: Indoor environmental quality is going to become more important going forward. We’re already seeing it in designs. We’re seeing individuals include what’s called “Pandemic Mode” for how the equipment or system should operate. Think of it as an emergency generator kicking on when you lose utility power. Well, when we get into a pandemic, how does my HVAC system need to operate differently?

The biggest change I see is related to the domestic manufacturing capacity for facemasks and respirators. As of now, the U.S. estimated production capacity for these products has exceeded the estimated domestic demand. This is a significant change from 2019 when approximately 75% of masks were imported.

– Thad Ptak, Ph.D., Ptak Consulting

In a “Pandemic Mode” scenario, a user can establish certain practices to improve IAQ with the threat of a virus in mind. This could mean adjusting the system to operate with the aim of moving air through a space by raising the temperature set point a degree. Or, a user could switch the fan to “always on” mode, rather than only running when the condensing unit engages to provide cooling or heating. Another option might be lowering the threshold on a demand-controlled ventilation system to bring in more outside air.

There’s a lot of different variations. One of our clients is actually looking at changing their design standard. In the beginning of this pandemic, they started adding filters where they could. Now they’re going to focus on a 12-inch deep, MERV-14 bag filter, because of the limited impact of pressure drop and fan energy. They installed one in a unit for six or seven months without pre-filters, based on where it was located. And so they’re looking at ways of, “Okay, what is going to be our optimal filter all of the time?”

That way they have no pandemic mode or regular mode for filters. It’s already pre-built and ready for it. We’re seeing a lot of those changes come through in the design and the owner side, to try and figure out how they can tweak their systems to improve their indoor environmental quality.

Behnam Pourdeyhimi: I believe we are not ready for another pandemic yet. Manufacturing innovations are badly needed, and we need a better approach to designing filters for masks.

The HVAC filters offer another major problem. The flow rates are high, and pressure drops have to be ultra-low, or good filters (MERV 13 and higher) cannot be used in existing infrastructure, since most are not capable of dealing with the high pressure drops.

It is not a question of if, but when, another global pandemic happens. In the absence of policies that encourage domestic manufacturing of PPE and other critical products, the shortage situation in the United States likely will be no different. In the absence of democratized manufacturing, low-income countries will continue to be at a disadvantage.

The status quo of PPE manufacturing is not advanced enough to shield the United States from the next viral outbreak definitively. Further manufacturing innovations are the path forward to more reliable, affordable, adaptable protection. Cloth masks will not be the solution and will be regulated perhaps using the new ASTM 3502, or equivalent.

As such, The Nonwovens Institute and its partners are developing manufacturing strategies and educational programs to help establish definitive minimum standards for manufacturing that would be scalable and easily reproducible.

FiltXPO 2022 will present three days of provocative debates, with five panels of global industry experts who will share pivotal ideas aimed at uprooting traditional industry perceptions. For more information, visit filtxpo.com.

* Portions of Dr. Behnam Pourdeyhimi’s responses for this roundtawble are based on a previously published article, “COVID-19 — Lessons Learned?,” which appeared in Textile World, July/August 2021, pages 18-21, https://www.textileworld.com/textile-world/features/2021/07/covid-19-lessons-learned/.

** International Filtration News is owned by INDA, Association of the Nonwoven Fabrics Industry (inda.org), organizer of the FiltXPO exhibition and technical conference.