President, National Air Filtration Association

President, ZENE LLC

Over the past several months, the world has faced some unexpected/unpredictable filtration challenges, such as the bushfires in the New South Wales region of Australia, which produced air quality that the Australian Environmental Protection Authority dubbed “the worst in the world.” And now, the coronavirus (COVID-19), which has been declared a global pandemic, the scope of which, at the time of this writing, we are still trying to determine. Both of these tragic events call into question how prepared filtration technologies and systems are in addressing emergency scenarios like, for example, wildfire-induced air pollution or viral outbreaks, like what we’re seeing the COVID-19.

To help us understand what the Australia bushfires and the coronavirus outbreak mean from a filtration perspective, we recently interviewed Tom Justice, the president of the National Air Filtration Association. In addition to his involvement with NAFA, Justice has served on a number of ASHRAE standards committees, been involved with ISO air filtration initiatives, and received lifetime achievement awards from NAFA and INDA, Association of the Nonwoven Fabrics Industry. Justice also holds several patents related to air filtration.

Matt Migliore: From a filtration perspective, how prepared are communities worldwide to prevent the spread and negative impacts of viral outbreaks, such as the coronavirus, and unexpected air quality scenarios, such as the recent Australia bushfires?

Tom Justice: The International Health Regulations Emergency Committee of the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” back on January 30th. During the ensuing weeks we have seen a run on facemasks, as well as panic buying of staple items, which has served only to make matters worse.

Also driving the demand for facemasks have been the massive brush fires, such as those in Australia.

C. Raina MacIntyre and Abrar Ahmad Chughtai of the University of New South Wales brought to everyone’s attention the unfortunate consequence of panic buying in countries where the risk of catching the virus is low.1 “The result ends up being a shortage of supplies which might not be available when we need them most.” They also brought out another consequence of panic buying: “It is important that we supply our health care workers with the best protection possible, for without them we lose our ability to fight the epidemic.”

MacIntyre and Chughtai pointed out that during the SARS epidemic, 21% of all cases globally were healthcare workers, a statistic which should be of concern to us all.

Bottom line, governments never seem quite prepared or willing to control the distribution of supplies during a crisis, however rationing may be the most reasonable solution.

So often the challenge is not can we filter the contaminant but rather can we get the contaminant to the filter. What this does is highlights the need for further research, as well as better guidance for the homeowner on how to get the most out of their air filters.

Matt Migliore: What sort of filtration technologies are currently available to help minimize the threat of viral outbreaks like the coronavirus and/or severe air quality events like the Australia bushfires?

Tom Justice: It is important to first understand how the virus spreads. Cross transmission can occur through direct contact, as when an infected individual comes in contact with a susceptible person through such means as touching or kissing. Indirect contact can occur when an individual touches a surface such as a doorknob or handrail which has been contaminated. Finally, airborne exposure occurs when respiratory droplets are released through such means as coughing or sneezing. Larger droplets fall to surfaces about 3 feet from the infected person.

This gives credence to the advice that one should maintain a distance of one meter or more from anyone suspected of carrying the infection. If one breathes in the droplets from the infected person, they risk catching COVID-19. However, once these larger droplets settle on nearby objects, COVID-19 can be spread when someone touches the surface and then touches their eyes, nose or mouth. Smaller droplets can remain airborne for hours and can be transported long distances through such vehicles as HVAC systems.

Considering these methods of transmission, HVAC filtration can be effectively used to combat airborne transmission of smaller particles, and facemasks can be effective when worn by those who are contagious. That said, the World Health Organization suggests that “COVID-19 is mainly transmitted through contact with respiratory droplets rather than through the air.”2

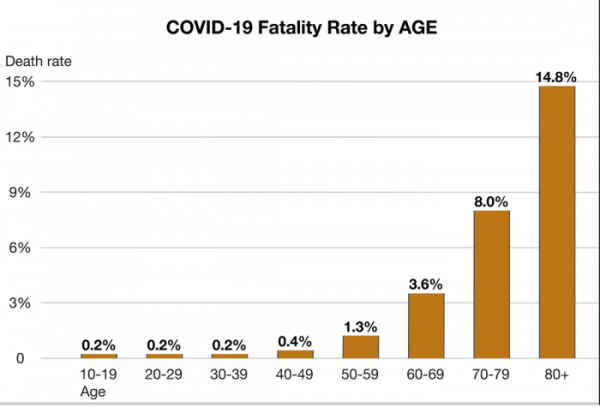

While the health impact of wildfires can be seen as chronic with long-lasting effects on human health, in contrast the effects of COVID-19 are very acute with a fatality rate that increases dramatically with increasing age, as shown here.

Matt Migliore: From a facemask and respirator perspective, how has this technology evolved in recent years to provide more effective protection in scenarios such as the coronavirus outbreak and/or during severe air quality events like what we we’ve seen with the Australia bushfires?

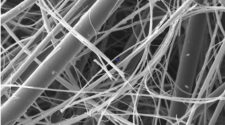

Tom Justice: Fine fiber technologies combined with more effective charging has allowed improvements to be made in facemasks, which provide better protection against smaller particles and less labored breathing. The technology is available to address the public health emergencies; however we lack the training to help the public understand how best to use the available resources.

Matt Migliore: Beyond facemask and respirator technology, what is happening on the air quality monitoring and air purification front to help address/minimize the impact of events such as the coronavirus and the Australia bushfires?

Tom Justice: Viruses are shaped by natural selection just as evolution shapes plants and animals. Over the near term, we will neither completely stop the occurrence of new viruses or the outbreak of deadly fires. We can however do a better job of changing the conditions, which are conducive to the development of new disease. For now what we can do is to educate ourselves on how best to respond to these threats to our personal health.

The best sources of information on Prevention and Treatment are the websites for the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO). For those looking for detailed information on airborne diseases, I would recommend ASHRAE’s recently reaffirmed Position Document, titled “Airborne Infectious Diseases,” which can be found on their website at ashrae.org.

Matt Migliore: There has been some research and technology emerging on the market that aims to remove CO2 emissions from the air in outdoor environments. Are there similar technologies focused on filtering smoke/particulate in scenarios like the Australia bushfires and/or in filtering airborne viruses?

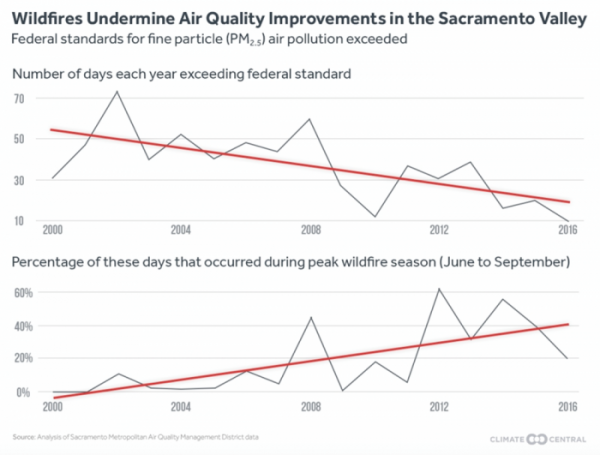

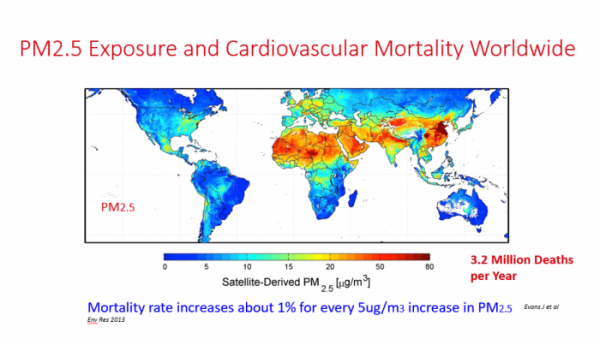

Tom Justice: California wildfires in 2017 released more than 200 tons of PM 2.5 particles. This number was based on calculations Sean Raffuse, an air quality analyst at the Crocker Nuclear Laboratory at University of California in Davis using estimates off of U.S. Forest Service models. To put this into perspective, he points out that this is the same amount of primary PM 2.5 that the EPA estimates come from California vehicles in a year, according to its most recent National Emissions Inventory. This has negatively impacted the improvements made in air pollution as shown here by the 2 graphs on PM 2.5 levels in the Sacramento Metropolitan Management District.

In 2017, William Fisk and Rengie Chan, Ph.D., with the Indoor Environmental Group, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, published research sponsored by the U.S. EPA on the health benefits and costs of filtration interventions that reduce indoor exposure to PM2.5 during wildfires. Their analysis estimated the health benefits expected if interventions had improved particle filtration in homes in Southern California during a 10-day period of wildfire smoke exposure. The interventions were projected to prevent 11% to 63% of the hospital admissions and 7% to 39% of associated deaths. Those interventions outlined included upgrading to high efficiency air filters (MERV 12), running the system fans continuously and use of a HEPA portable air cleaner.

Matt Migliore: From an indoor air quality perspective, how equipped are today’s buildings to provide effective protection for their inhabitants in the event of a severe air quality event like the Australia bushfires and/or in filtering airborne viruses?

Tom Justice: Research by Siegal, et.al., at the University of Toronto and funded by ASHRAE studied the relationship between efficiency and the overall actual performance of the filter. The study collected data from 20 homes over a year-long period of time. The conclusions highlighted “the fact that filters are one part of the complex residential environment and their performance cannot be extrapolated from laboratory tests alone.”4 So often the challenge is not can we filter the contaminant but rather can we get the contaminant to the filter. What this does is highlights the need for further research, as well as better guidance for the homeowner on how to get the most out of their air filters.

Matt Migliore: Looking into the future, how do you see filtration and/or monitoring technology evolving to more effectively address events such the Australia bushfires and the coronavirus outbreak?

Tom Justice: I think that we will see significant changes not in the filters so much as how we transport the air and the contaminants to the filter. Changes are most needed in residential structures and related HVAC systems. When one asks why filters have typically been installed in central HVAC systems in North America, the answer is quite simple: Because it was always convenient. The only thing that really matters is how good of a job can we do in lowering particulate count in the living space. And in this respect many systems are not performing adequately.

Related article:

References

- “Coronavirus: How effective are face masks? Should we be worried about the shortage?” Considerable, https://www.considerable.com/health/coronavirus/coronavirus-face-masks-effective/.

- “Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19),” WHO, https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses.

- “Health benefits and costs of filtration interventions that reduce indoor exposure to PM2.5 during wildfires,” John Wiley & Sons Ltd, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ina.12285.

- “Indoor Air Quality and Energy Implications of Filters in Residential Buildings,” ASHRAE Journal, Vol. 61 No. 11, Nov. 2019

![Figure 1: Heat Exchanger Proventics GMBH.[22]](https://www.filtnews.com/wp-content/uploads/IFN_2_2024_crimpedmicrofiberyarns_Fig.-1-Heat-exchanger-225x125.jpg)