The American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) formed an Epidemic Task Force (ETF) in March 2020. The aim of the group is to provide building designers and operators a point of trusted information and guidance for optimizing their facilities amid the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as for a future state where viral contagions are a more prominent concern.

The ETF was formed with three main points of priority:

- addressing the immediate threat of COVID-19,

- recommendations for the second wave of the pandemic; and

- strategies for the next epidemic.

One of the outcomes of the ETF is its Building Readiness Guide, which outlines best practices for facility operators to manage their buildings during the pandemic. As the performance of many HVAC systems in buildings is still being evaluated, the ETF has updated its HVAC guidelines throughout the pandemic to help operators mitigate the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and ensure optimum efficiency of their systems. The guidance addresses the tactical commissioning and systems analysis needed to develop a Building Readiness Plan and overall improvements to a system’s ability to mitigate virus transmission.

Filtration considerations for ensuring building readiness

The most recent update to the ETF’s Building Readiness Guide considers the details of what the system can handle in light of its recommendation to employ MERV 13 filters. While MERV 13 is being recommended for systems that can support this level of filtration, not all HVAC systems are designed for MERV 13, and MERV 13 is not a panacea for mitigating the threat of SARS-CoV-2 in the indoor environment.

“The Building Readiness Guide includes additional information and clarifications to assist designers and commissioning providers in performing pre- or post-occupancy flush calculations to reduce the time and energy to clear spaces of contaminants between occupancy periods,” says Wade Conlan, ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force Building Readiness team lead and Commissioning and Energy Discipline Manager for Hanson Professional Services, Inc. “New information includes the theory behind the use of equivalent outdoor air supply method for calculating the performance of filters and air cleaners in series, and filter droplet nuclei efficiency that help evaluate the systems’ ability to flush the building.”

Major updates to the ETF’s building readiness guidance include:

- Pre- or post-flushing strategy methodology: The strategy has been updated to include the use of filter droplet nuclei efficiency, which is the overall efficiency of filter based on predicted viable virus particle sizes in the air (based on Influenza A), to assist in determining the impact of the filter on the recirculated air to create equivalent outdoor air. This allows the filter efficiency as a function of particle size, using ASHRAE Standard 52.2 test results, to be estimated based on the expected size distribution of virus-containing particles in the air.

- Flushing time calculator: There is now a link to a Google Sheet that can be downloaded for use to help determine the available equivalent outdoor air changes and time to perform the flush. This sheet is based on a typical mixed air handing unit (AHU) with filters, cooling coil, with potential for in AHU air cleaner, and in-room air cleaning devices. (The Google Sheet can be downloaded at http://bit.ly/ashrae-airvolume.)

- Heating season guidance: The guide now includes data to consider for heating of outdoor air and the potential impact on pre-heat coils in systems.

“The Building Readiness Guide was [initially] focused on helping owners switch to a low occupancy or unoccupied mode and reduce energy without creating other issues (think mold),” says Conlan. “The BRG then looked to provide the practical guidance on how to analyze the HVAC systems and to determine how the mitigation strategies could be implemented for the HVAC systems. The strategies are designed to reduce the virus transmission. Filter efficiency could be one. Increasing outdoor air beyond code is a strategy. But not all strategies work for all HVAC systems, so you have to evaluate the strategies within the context of the system.”

Conlan says the ETF updated its guidance with the aim of helping operators understand what filtration MERV level their systems can handle and how they can achieve adequate air quality in facilities where MERV 13 is not an option. “There are a lot of scientific aspects to determine the right balance of outdoor air and filtration,” says Conlan.

Some questions to consider include:

- How much outdoor air can you get?

- Can the fan deal with the pressure drop of a higher-rated filter?

- Can the filter type fit in the HVAC system?

- How does the external climate impact system parameters?

Conlan says one of the main concerns for building operators is getting into a “belt and suspenders” situation where the solution is over-engineered to provide more outdoor air than is necessary and/or more filtration than is necessary, as this will result in added/unnecessary cost.

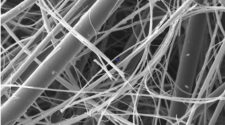

In addition, Conlan says proper installation of the filter is critical to its performance, as studies show that less than a 0.4-inch gap can make a MERV-15 filter operate like a MERV-8.

“Another factor that has been discussed is the difference between MERV and MERV-A-rated filters,” says Conlan. “MERV-A-rated filters require the electrostatic charge to be dissipated before it is tested, while MERV testing allows the filter to have an electrostatic charge, which enhances its particle capture performance under test. However, in a real-world scenario, the electrostatic charge is naturally reduced as materials hit the filter, and it is impacted by the relative humidity of the surrounding environment.

For many building operators, Conlan says this new focus on IAQ is a shift. While labs and hospitals already have a strong understanding of air quality, office buildings and schools have traditionally focused on the comfort of building patrons and minimizing energy consumption. And issues such as old equipment and operating costs further complicate the issue for some.

Conlan says many school districts, for example, are woefully underfunded and have equipment that has far outlived its useful life. Even some airports, he says, have been found to have HVAC systems that are not capable of providing the level of air quality required to minimize the threat of virus transmission.

Conlan says many school districts, for example, are woefully underfunded and have equipment that has far outlived its useful life. Even some airports, he says, have been found to have HVAC systems that are not capable of providing the level of air quality recommended by the ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force to minimize the threat of virus transmission. And supplementing an old HVAC system with outdoor air means more operating cost, as it costs more to condition outdoor air than it does to condition return air.

For such facilities, a sign of hope can be found in the area of technological innovation. “There is a lot of new technology being developed to help improve the HVAC systems ability to reduce virus transmission,” says Conlan. “We just need to have enough studies applicable to the installation and building spaces and peer-reviewed research to make an engineering decision to use those technologies.”

“I haven’t seen a silver bullet yet,” says Conlan, as he warns against the PR machines behind many of the technologies coming to market today that profess to address virus transmission within HVAC systems. “Looks great, sounds great, but when you talk to IAQ experts, there is a lack of proven study and test results to verify performance. You have to have clarity on the test methods, procedures and complete result data sets.”

Next steps

The ETF is providing information based on what it knows today, and the information and research on SARS-CoV-2 within the HVAC systems will help improve the guidance for today and for the next epidemic.

“There will be systems that require a lot of work to get there,” says Conlan. “But there is a better understanding and awareness. People are thinking about [air quality] at least, which is pointing us in a better direction.”

The ETF is an ad hoc organization that is aligned with the Environmental Health Committee and serves at the pleasure of the ASHRAE president. The Task Force, Environmental Health Committee, Technical Council, ASHRAE Society president, Chuck Gulledge, and ASHRAE Society president-elect, Mick Schwedler, will decide at the end of the ASHRAE year, June 30, whether the ETF will continue on and in what form.

ASHRAE is being mindful of the need to incorporate its guidance from the COVID-19 pandemic into its core frameworks to ensure preparedness for future epidemics.

Meantime, as the ETF continues its work, Conlan says, “Stay tuned for updates, stay safe, and stay upwind.”

To view the complete ASHRAE Building Readiness Guide and other COVID-19 resources, visit ashrae.org/COVID19.