Today, the reverse osmosis (RO) industry has reached such a large scale that it has significantly impacted the daily lives of most people and affects to almost all industries worldwide. At a forecasted compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.2%, the global market for RO system components in water treatment is expected to reach $32.0 billion by 2029, according to BCC Research.

However, like most other industries, the fast-growing RO business will also face challenges from environmental issues. However, these challenges could become the driving force behind technological innovations and new opportunities if we tackle the problems correctly.

One of the major environmental issues is RO membrane waste. The world consumes tens of millions of RO membrane modules every year, and most are discarded to end up in landfills.

From a global perspective, China is the largest consumer of RO membranes, accounting for more than one-fourth of the global market, and the second-largest producer, only after the United States. A research study from the Beijing Institute of Technology estimates that about 5.5 million 8-inch RO membranes have been discarded each year in China, accounting for 27.5% of the world’s total. Therefore, solutions to deal with the RO waste problems have become a top priority. The most promising solutions to this issue include regeneration, graded utilization, conversion, materials recycling, and improvement of membrane durability.

Regenerated Reverse Osmosis Membranes

Discarded RO membranes can restore a substantial portion of their original performance after being cleaned and subsequently subjected to chemical or physical treatment. These regenerated membranes exhibit desalination performance between that of nanofiltration (NF) and RO membranes, with permeation performance nearly restored to the original level.

With various modification or surface treatment methods, such as coating the membranes with natural sericin protein, the desalination rates of the regenerated RO membranes can exceed 90%, according to several studies. These regenerated membranes are suitable for some less-demanding applications, such as partial desalination, RO pretreatment, material separation, and concentration.

Currently, research and development continue to improve the quality of regenerated RO membranes. The main development efforts focus on both physical modification methods, such as adsorption, coating, and doping (with nanoparticles), and chemical modification, such as chemical coupling and grafting.

Commercial practice has demonstrated that regeneration of RO membrane waste is not only environmentally friendly but also economically feasible. Runbang, a North China-based RO membrane

recycling company, illustrates its business model with an example:

- A RO user bought a new RO module at $3,000. After three years of the module’s service life, they sold the used module to a waste collector for $15.

- The collector sold the used module to a recycler at $30.

- A testing service provider tested the collected modules for the recycler to determine if they could be regenerated, at an approximate cost of $70 per module.

- A machine maker sold testing equipment to a testing service provider for approximately $7,000.

- The recycler cleaned and repaired the regenerable RO module, then sold the regenerated module to a user for approximately $1,500, which secured the recycler’s main profit.

- The recycler purchased an interfacial polymerization coating machine for $40,000 from a machine manufacturer.

- The recycler broke down the non-regenerable materials into plastic pellets, such as polysulfone (PSF), polyamide (PA), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and sells them to a regenerated pellet user at about $9. Although this is only a small amount, it does offset part of the cost – for example, a recycler sold 20 metric tons of regenerated PSF pellets to an automotive part manufacturer and generated a revenue of $40,000 per month.

- A water treatment plant could save an average of 25% on costs by purchasing half-price regenerated RO modules instead of virgin modules. However, the regenerated ones have a relatively shorter service lifespan.

Conversion

RO membranes, which consist of a porous support layer and often a PA separation layer, can be converted into ultrafiltration (UF) or microfiltration (MF) membranes by selectively oxidizing and degrading the PA layer. For instance, NaClO-treated RO membranes have achieved permeabilities and retention performance comparable to those of commercial UF membranes. Potassium permanganate treatment can remove the active layer entirely, enabling conversion to MF membranes suitable for pretreating wastewater, which achieves high turbidity reduction and high suspended solids removal.

Additionally, through the appropriate treatment of discarded RO membranes, their separation properties can be modified to achieve NF performance. NF membranes have a performance range between RO and UF membranes. Studies have demonstrated that discarded RO membranes often exhibit twice the water permeation flux of new membranes, while their salt rejection rate decreases to 35–50%. Their mass transfer characteristics are comparable to those of NF membranes, making them suitable for applications such as seawater pretreatment, brackish water desalination, preparation of isotonic or hypertonic solutions, and artificial seawater production for coral research. Chemical modification approaches – such as immersing discarded membranes in polyamine solutions or treating them with NaClO – have been shown to adjust retention characteristics, flux, and fouling resistance to match those of commercial NF membranes.

Discarded RO membranes can also serve as structural supports for fabricating anion exchange membranes. For example, by removing the PA layer and coating the supports with anion exchange resin blends, regenerated membranes are produced that have high selectivity – comparable to commercial products- and a high desalination rate for brackish water.

Graded Utilization

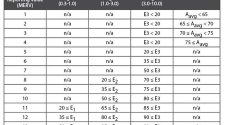

Graded utilization is a design where fresh and high-rejection membranes are placed at the upstream end of the filtration system, with older and low-rejection membranes placed behind it. This approach, similar to the Internal Segregated Design (ISD), reuses older membranes instead of discarding them. Additionally, this design can also reduce permeate conductivity and pressure differentials in an RO system, thereby extending the membrane’s service life.

Improvement of Membrane Durability

Extending membrane’s service life not only is critical for cost reduction but also help increase the RO membranes’ lifespans and thus reduce the amount of discarded waste. Enhancing resistance to fouling and chlorine degradation minimizes the need for frequent cleaning and replacement, leading to improved system stability and reliability, which in turn results in a longer service life.

Membrane fouling remains one of the principal limitations of RO membranes in real-world applications. Current research and development efforts to mitigate fouling focus on three main strategies: (1) surface modification technologies, such as grafting hydrophilic groups or applying anti-fouling coatings, which enhance surface hydrophilicity and thereby reduce contaminant adsorption; (2) optimization of operating conditions, including adjustments to feedwater quality, pressure, and flow rate, to minimize fouling and extend membrane lifespan effectively; and (3) development of self-cleaning materials, such as photocatalytic and antibacterial membranes, which can degrade or inhibit foulant accumulation under specific conditions.

The poor chlorine tolerance of RO membranes could limit their use in certain applications and reduce their service life. Current development efforts focus on three key areas: (1) material modification, where chemical modification to PA membranes – such as introducing chlorine-resistant functional groups or incorporating antioxidants and stabilizers – enhance chlorine resistance and long-term stability; (2) process innovations, including refinements to the interfacial polymerization process, such as the use of buffer layers to better control polymerization rates, which produce membranes with improved chlorine tolerance and performance consistency; and (3) integration with complementary technologies, such as ultraviolet disinfection and activated carbon adsorption, which reduce residual chlorine levels in feedwater, thereby mitigating membrane damage and extending operational lifespan.

Materials Recycling

As mentioned above, PSF, PA, ABS, and PVC can be recovered from RO membrane waste. Other examples include converting waste membranes into carbon materials through pyrolysis, which can then be used as adsorbents or incorporated into construction materials such as bricks, and mechanically grinding waste membranes to produce fillers for concrete.

Energy Saving

In addition to waste management, another environmental issue the RO membrane industry faces is energy saving. RO uses around 2.5 to 3.5 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per cubic meter of treated water. As global production of desalinated water through RO technologies reaches tens of billions of metric tons, the associated energy consumption has risen to the scale of hundreds of thousands of gigawatt-hours (GWh) a year. High energy consumption results in high greenhouse gas emissions, which undoubtedly have a negative impact on our environment.

Currently, the RO industry mainly works on two areas to reduce the energy consumption:

Development of novel materials: Advances in PA chemistry and composite materials can improve membrane performance, reduce required operating pressure, and consequently lower energy demand. For instance, incorporating nanoparticles into polyamide matrices by nanotechnology can enhance membrane structure, increase water flux, and reduce energy consumption.

Optimization of membrane structure: Innovations in membrane architecture – such as increasing porosity or tailoring surface properties – can boost water permeability and reduce the required operating pressure. For example, RO membranes supported by vertically aligned carbon nanotubes have demonstrated both higher water flux and superior salt rejection rates.

Energy savings not only mitigate the negative environmental impact of RO but also reduce the operational costs of RO systems and increase their competitiveness in the water treatment market. Therefore, it has become the hottest topic in the research and development of RO technologies.

References

- Siyi Huang, Changhao Liu, Haixia Wu, “Life cycle sustainability assessment of end-of-life reverse osmosis membranes management options,” Desalination Volume 613, October 15, 2025, 119050